To fully understand the ecology of Point Pleasant Park, and to get a more complete view of its present state and the health of its forest and its trees, it is helpful to understand both its natural history and its history of human occupation and management.

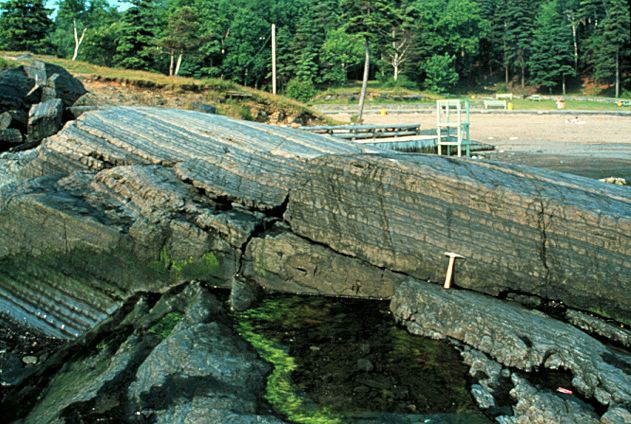

The first and foremost influence on its soils is the underlying rock - a Meguma group of the Halifax Formation of slates, schist, and migmatite that were metamorphosed from sedimentary rocks in the Ordovician period about 450 million years ago.

|

| Black Rock Beach rock formations |

The last glaciation in Nova Scotia ended about 10,000 years ago. The ice movement in the Halifax area scoured off the previous soils, revealing the bare slates and quartzites below, leaving only small pockets of glacial till.

|

| PPP bedrock showing striations with hammer for scale |

First, lichens, then small plants, using rain-dissolved minerals, slowly

built up a thin scurf of soil from previous generations of plants dying

back and from wind-carried particles. For 10,000 years, successions of

small plants, shrubs, and then trees produced a fairly thick, but

relatively low, forest cover on a still very thin and poor acidic soil,

known as the Halifax/Bridgewater Series.

The next major influence on the Park's health was European settlement. In

1749, Edward Cornwallis weighed anchor offshore. He named the peninsula

Point Pleasant; at that time it supported a relatively young, thick and

healthy forest probably of spruces, pines, hemlock, white pine, fir, maple

and other species typical of the Nova Scotian Acadian forests.

While the Mi'k Maq used the area as a summer fishing camp, their

technology, aside from fire,would have had little impact on the

natural forest. Cornwallis introduced to the Halifax peninsula 4,000 soldiers and settlers with an insatiable need for wood. They brought with them metal saws, metal axes,

shovels, and pick-axes. They also introduced heather, other unknown

flora, seeds, fauna, and most likely insects.

Cornwallis had been charged by the British Government to create a

settlement both military and civilian, but first he had to clear Point

Pleasant of trees. He sent a letter back to Britain, stating, "...the land

was terrible because

of the extensive forest. As there was not one yard of clear ground, Your

Grace will imagine our difficulty and what work we have to do."

His first clear-cut was of 12 acres on the southern shore of the Park.

But afterwards, because the trees were gone, the site was found to be too

exposed to the wind and weather, and soon, too uncomfortable and cold.

Also, the shallow, rocky shoals off the point (the 'hens and chickens')

were inconvenient because they prevented close-in mooring of ships.

So the settlers, with some of the military, moved up-harbour to found

Halifax at the base of Citadel Hill. The troops continued construction of

fortifications in Point Pleasant. There were more clear-cuts (for cannon

sightlines and ease of construction), and also extensive quarrying of

stone both for roads and for each fortification. The first forts were of

logs, earth, and stone, with wood-burning fireplaces. Later, furnaces

were added for heating/smelting cannon shot; for these, hardwoods were

needed for fuel because of the higher temperatures required.

There were a total of seven fortifications constructed. Most were rebuilt

four or five times over 200 years, with consequently more clear-cuts for

each renovation, and more excavation of rock and stone for ditches,

embankments, walls, and roads. There were massive earthwork trenches and

embankments at some of the forts - such as Ogilvie - damaging trees and

roots, and disturbing and redistributing the soil.

A continuous wood supply was also required for cooking fires and for

heating. The wood was supplied by the

Point's forests, and the paths for gathering supplies and wood were made

permanent by their continued use. The shore forts were subject to wind,

wave, and storm erosion because the protective trees were gone. The

'Battery' fort for instance, just west of Point Pleasant, was damaged in

1895 and was falling into the sea. It was moved further along the

Northwest Arm shore, with the consequent necessity for a large, new area

clear-cut around it.

From 1749 until the early 1900s, Point Pleasant was subjected to

continuous biomass extraction and major disturbance of trees,and their

roots and soil - for forts, firewood, kindling, furnaces, gates, fencing,

and lumber; and removal and displacement of rocks for forts, roads, gates,

walls, and trenches.

European Settlement and the Park's Forest

Images Showing Areas Cleared of Trees for Various Forts in Point Pleasant Park Click to see

larger image (courtesy Gary

Castle)

Some Historic Highlights of

Point Pleasant

Gatekeeper's Lodge (courtesy Gary

Castle)